By: Richard L. Smith

In a time when the public is increasingly scrutinizing the justice system’s sense of balance and fairness, the case of Anthony Salters raises serious questions about proportionality and punitive overreach.

Salters, a well-regarded public school educator and political figure in Union County and across New Jersey, recently completed a prison sentence, not for fraud or violence, but for a misdemeanor: failing to file a tax return in 2017.

On the surface, the offense appears minor — a lapse in paperwork, perhaps reflective of negligence rather than criminal intent.

Would the penalty, scrutiny, and rigorously coverage of this case have been the same if Anthony Salters were not a public employee or the influential, well-connected statewide Hillside Democratic Committee Chairman?

Interestingly, many politicians must contend with a public perception that they are guilty until proven innocent when facing legal matters.

Yet Salters was handed a six-month federal prison sentence, serving four months behind bars before being released in mid-February.

The punishment, critics say, is not just excessive — it’s a glaring example of a system that sometimes punishes the person more than the actual crime.

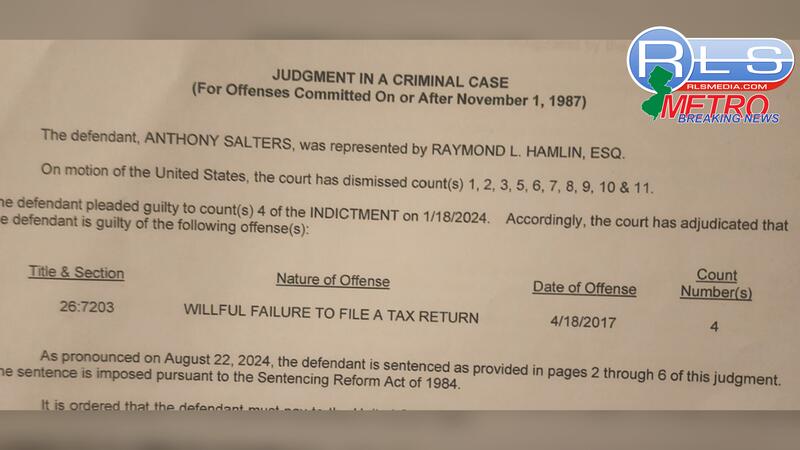

Ultimately, Salters pleaded guilty only to a single misdemeanor count of “willful failure to file a tax return,” a violation of Title 26, Section 7203 of the U.S. Code.

For this, I found that he was sentenced under the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 and assessed a $25 fine — alongside a prison term that even some legal experts say would have been better suited for probation or a financial penalty.

The New York Times reported on October 11, 2024, that Mr. Salters had pleaded guilty to tax fraud; however, this information was inaccurate according to court documents obtained by RLS Media.

Salters’s defense attorney, Raymond L. Hamlin, emphasized that no New Jersey law bars his client from continuing in his role as a homebound teacher with Hillside Public Schools.

And rightly so. According to the New Jersey Department of Education, disqualifying offenses for school employment include severe crimes such as homicide or sexual assault, not tax-related misdemeanors.

Salters’s continued employment, therefore, is both legal and appropriate. Still, public reaction has been swift and divided. Critics question how someone with a criminal record — however minor — can maintain a public school position.

But supporters argue this is precisely the kind of offense that should not destroy a man’s career, especially when the punishment has already been served. In a letter to his coworkers, Salters described his incarceration as a "total waste of taxpayer monies" and a "tremendous inconvenience."

It’s a sentiment that resonates far beyond his personal experience. Sending someone to prison — at taxpayer expense — for what was essentially a non-violent, first-time tax violation arguably achieves little in terms of deterrence or rehabilitation.

The U.S. justice system is already overcrowded, under-resourced, and frequently criticized for targeting lower-level offenders with disproportionate consequences.

Salters' case is a prime example of that. Moreover, the public’s interest in the case appears to be rooted more in optics than substance.

Would the conversation be the same if he were not a public employee? Why are we more comfortable allowing someone to remain in office after documented ethical violations, yet we question a schoolteacher’s employment after a misdemeanor, especially one that has been adjudicated and served?

It is worth noting that Salters makes $80,000 annually, and school officials have not indicated that he was to forfeit any compensation during his brief incarceration.

According to Hillside Township district officials, the role is a newly created one for the 2024-2025 school year, raising another point of contention: Should a public institution be judged for standing by an employee who made a legal misstep but was never convicted of a crime that disqualifies him from serving?

I must be clear that this case is not about ignoring wrongdoing. Rather, it’s about fairness, the proportionality of punishment, and the ability of individuals to move forward after paying their debt to society.

Anthony Salters made a mistake. He admitted it, took responsibility, and served his time. To call for his dismissal now would be to inflict a second, unjust punishment — one that neither the law nor common sense demands.

As the public continues to wrestle with how justice should be administered and how redemption should look, Salters's case offers a powerful opportunity to reflect: Are we truly interested in rehabilitation, or just retribution?