By: Phyllis Bivins-Hudson

One of the many celebrations in November is Veteran's Day.

Let us consider the Unsung Veteran Soldiers, whether male or female, in this blog.

For the most part, research yields a cursory look at some notable and not-so-notable veterans. However, there are a vast number of notable and not-so-notable veterans who go unrecognized because of who they were or are.

For the most part, research yields a cursory look at some notable and not-so-notable veterans. However, there are a vast number of notable and not-so-notable veterans who go unrecognized because of who they were or are.

They are my Unsung Soldiers.

They are the many Black American Soldiers who never received their praise, their thanks, or their roses while in the service or even when they were no longer enlisted.

First of all, let’s consider some of the facts. During WWII, more than one million African American men and women served in every branch of the United States Military.

The irony is that while these soldiers fought abroad, they were also fighting at home for basic freedoms that white Americans did not have to consider.

At home, they faced racism and segregation; abroad, they faced fascism but also had to contend with the continued racism and segregation from the very soldiers with whom they served.

Despite these demoralizing obstacles, African-American men and women fought for America with distinction in every theatre of the war.

Forced to be segregated into separate units because of the belief that somehow, these men and women were incapable or not as capable as their white counterparts, they refused to allow the dispiriting behaviors of others to impede their abilities to shine.

In fact, they formed some very famous Black units, including the 332nd Fighter Group, which took “down 112 enemy planes during the course of 179 bomber escort missions over Europe, and the 761st Tank Battalion, which served in General George S. Patton’s Third Army."

But there were some who recognized and vocalized the bravery and skill of many of these unsung soldiers. For instance, Major General Willard S. Paul of the 26th Division “singled out the 761st for special praise after its first action in France by writing, “I consider the 761st Tank Battalion to have entered combat with such conspicuous courage and success as to warrant special commendation.” (WWII The National WWII Museum New Orleans, Article, February 1, 2020).

But there were some who recognized and vocalized the bravery and skill of many of these unsung soldiers. For instance, Major General Willard S. Paul of the 26th Division “singled out the 761st for special praise after its first action in France by writing, “I consider the 761st Tank Battalion to have entered combat with such conspicuous courage and success as to warrant special commendation.” (WWII The National WWII Museum New Orleans, Article, February 1, 2020).

Furthermore, our Unsung Soldiers also served in other positions throughout the armed forces. They were nurses, engineers, truck drivers, gunners, cooks, and paratroopers.

These aforementioned units were more well-known, however, some others who were not as notable included the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions, who also fought in the European and the Pacific theatres of war. And there were more.

The point here is to recognize the Unsung Soldier (who is generally Black) during this year’s Veterans Day celebration.

Think about him or her when you consider what to do this Veterans Day.

Have a conversation with your family. Ask them to share stories about those who have gone on but who fought gallantly in a war that was not theirs and with soldiers who neither respected them nor recognized them as men and women with the same and, in many cases, more capabilities than their counterparts.

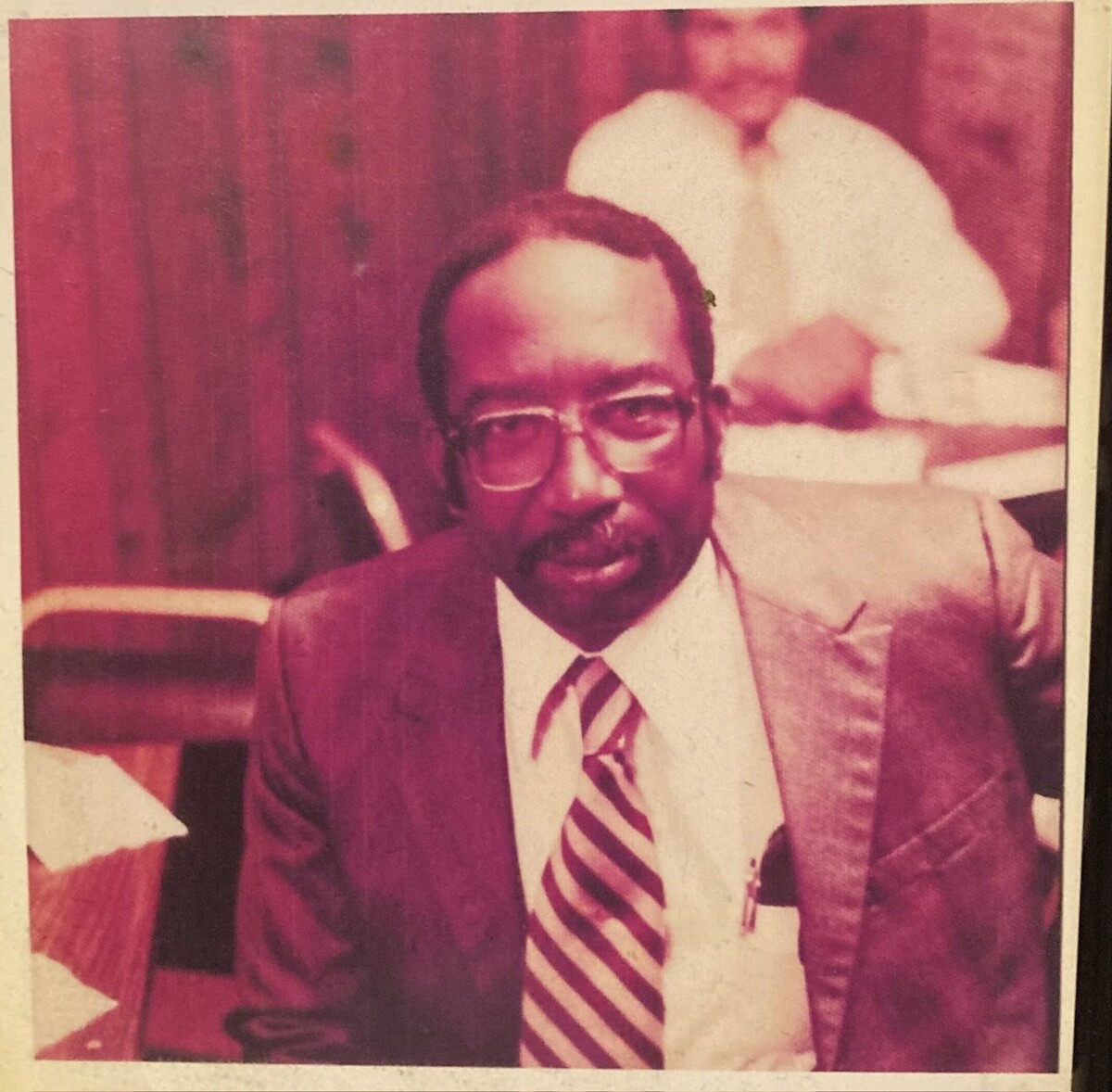

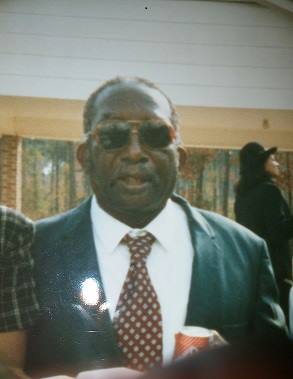

Now, let’s talk for a moment about a WWII veteran to whom I was fairly close, my late father-in-law, Wade Hudson, Sr. While his time in the army may not have been seen by others as significant, his family was very proud of this distinction.

Mr. Hudson served his country during a time when the Black Soldier was willing to serve his country but was rejected by his fellow white soldiers.

His story, out of his mouth when shared with his family, was engaging and riveting. To help tell his story, I enlisted commentary from his oldest son, Wade, Jr., who was present during a very interesting and somber moment when their dad, my father-in-law, held us spellbound as he told his story as it was being recorded in our minds and on an electronic device.

His story was told without bitterness or malintent. He simply spoke his truth relative to his experience.

Mr. Hudson was believed to have enlisted in the army. The following is the conversation that transpired between his son, Wade Jr. (my brother-in-law), and me.

Mr. Hudson was believed to have enlisted in the army. The following is the conversation that transpired between his son, Wade Jr. (my brother-in-law), and me.

Me: Wade, we know World War II was a global conflict that lasted from 1939 to 1945. We also know that the draft started in 1940 and lasted until 1973, but as you have stated, you believe your father enlisted into the armed forces, and in his case, the United States Army, rather than being a part of the draft.

For those who may be wondering about the difference, enlisting means you volunteered to join whichever branch of the armed forces you choose, whereas being drafted means you are selected by the government to serve where they want you to serve.

So, enlisting was significant because it was a choice, and during that time, Black people didn’t have a lot of choices. But when your father made his decision, did he share impressions about how he relayed the information to his mother and friends?

Wade: I remember him saying that his mother encouraged the boys to join because she felt it was a way for them to better help themselves and her. And after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, America entered the war.

Nationalistic fervor consumed the land. Most men, young and old, Black and White, felt it was their duty to join the military to defend “their” country. I emphasize “their” because Black Americans weren’t treated as full citizens.

Me: Thinking that enlistment and serving his country would be a conduit for improving his life makes sense.

And often, that may have been the case. On the other hand, did he discuss how he imagined military life would be before he joined?

Wade: No, he didn’t, not specifically. But I believe he had few expectations. It was a new experience for him, leaving a rural environment and entering a world that was foreign.

Me: What were some of the reasons your father joined the military? How did he choose the branch of service?

Wade: Most Black men, at least in that area of Louisiana, joined and were encouraged to join the army. One of my uncles did join the Navy. The military, as in the rest of the country, was segregated. In spite of Black Americans’ heroic efforts in past wars, such as the Revolutionary War, Civil War, and World War I, their mental capability and bravery were questioned.

Most were relegated to what were considered more menial jobs in the military. When they were allowed to fight and assume more “meaningful” positions, they distinguished themselves. There are countless examples of their bravery. Even today, we are learning more about the role Black Americans have played in the history of the US military.

Me: What about his perceptions about home and abroad, did they change after serving in the war?

Wade: I think he came to accept that racism was in the military just as it was in the country at large. As I stated earlier, the military, at the time, was extremely segregated.

Me: That had to be an awful feeling to know that you were fighting in a war for your country, yet could not find common ground around the bigotry that existed at home and then abroad.

War is hard enough, and then having to adjust to the existing racism provided a double whammy. But did your father ever talk about adapting to military life?

Wade: He talked more about his experiences, which, I guess, adapting was included indirectly. I think there was a strong sense of community among Black soldiers. They stuck together, supported each other, and stood up against the racism they faced together.

Me: Although we may not all agree that there were some advantages to being in the service, we do know that technical skills and travel were among the benefits. That said, where did Mr. Hudson travel during his service during WWII?

Wade: He served in England, Northern Italy, and Northern Africa. At least those are the places he shared with us. I think having an opportunity to have experiences outside the United States provided my father and other Black soldiers with another view of themselves. Racism in foreign places was not as overt and encumbering as it was in the United States. But, after the war ended, they had to come back “home.”

Me: There were other perks too. For instance, hearing from the people back home, especially if the enlisted man or woman had been gone for a long time. Did your dad stay in touch with his family?

Wade: Yes, he stayed in touch, especially with his mother and my grandmother. And he often sent money back to her. As for his time in the war, once he left the States, I believe he didn’t come back until the end of the war.

Me: War is such a devastating series of events. Did your dad ever describe how he felt coming home from combat?

Wade: No. But I know he was happy to return home when so many others lost their lives or were injured. But, I’m sure he had to find peace with what he had contributed to save and protect the United States with how he was treated once he returned home, especially returning to a small town like Mansfield, LA, where Jim Crow had a suffocating grip on Black people.

Me: I’m sure there are people who want to know that in spite of the racism, in spite of the actual fighting in the war, were there times when perhaps he and his comrades did things together that were not a part of the war?

Wade: Yes, there was a strong fraternity among the Black soldiers. They went to town to enjoy themselves together when they were off duty, usually drinking and trying to “pull the girls.” Of course, they brought their culture with them, their ways of expressing themselves, enjoying themselves, and dealing with the racism they encountered daily.

Me: (Laughter) When did your father leave the military? Did he share that process with you? Did he find civilian life difficult?

Wade: I don’t know the specific date he left. The war ended on September 2, 1945, when Japan surrendered. Germany surrendered in May 1945, and some soldiers who had fought in Europe began coming home.

My father never talked about transitioning to civilian life to me. But I think he found a way to settle back into small-town life. He met my mother, and they were married in April 1946.

Me: Once Mr. Hudson’s term was up and he returned home, did he talk about any help he may have received from the government during his transition back to civilian life?

Wade: No, he didn’t. But I know he benefitted from the GI Bill, which paid for him to be trained as a mechanic.

After completing the training, he and a friend opened a mechanic shop that folded after a year or two. Black soldiers, in general, did not benefit from the government support as White soldiers did.

Government support for returning soldiers and their families was responsible for helping to establish the middle class in this country and fueling the growth of suburban America. Things changed very little for Black soldiers like my father.

Me: It must have felt great to be a Black business owner during that time. It’s too bad his business failed, for whatever reason. But did he have advice for you, your siblings, or others about enlisting in the military?

Wade: He felt strongly that being in the military was a good thing. “It’ll make a man out of you” was what he often told us. He also said it was where a young man could go to get a trade. But I’m sure he had to be hurt by the unfair treatment, too, while he was in the army and after he came home.

Me: I’m sure there were many who did get a trade and may have been able to pass these skills down to their sons and/or daughters. But on another note, when you talked to your father about his experience, were you able to get any impressions about how the military affected him?

Wade: Despite racism and discrimination, my father always expressed a fondness for his time in the Army. He felt it allowed him to see different parts of the world. He also felt he was a part of helping to win the war. You know, it’s part of that duality that Black people are forced to embrace in order to survive.

Me: Was there anything that you know of that was particularly difficult for your father to communicate to family and friends about his military service?

Wade: I think, like most veterans, he never shared the horror of his experiences during the war. Those experiences, obviously, affected them tremendously, and in ways I don’t think many were able to conceptualize. They were encouraged to man up and deal with whatever the challenges like men. To not do so meant that you were weak. Remember, this was the 1940s.

Me: What else would you like to add to this conversation?

Wade: I would like to talk about the war’s goal, achieving freedom over tyranny, and juxtapose that to the lack of freedom for the returning Black GIs and their people. Many returned to face violence and tyranny in the country for which they defended. They fought for freedom, and they didn’t have it themselves.

Me: And that sad statement, in many ways, still rings true today. Wade, thank you so much for contributing to this blog. You have made this real for me by humanizing at least one of the Unsung Soldiers who lived and walked among us not so long ago. In fact, Mr. Hudson passed away in 2015, living to be 96 years old.

To all my followers, thank you for your engagement with this story. I hope you will take the time this Veterans Day to salute a special veteran among you. A veteran who perhaps is not known by many or who has never received his accolades.