“You know, everyone thinks when you play for the Yankees, you’re a millionaire,” says Cullen. “But I was only making $7,000.” -John Cullen

A former New York Yankees pitcher residing in Butler, NJ, is among the 504 retirees who don’t receive MLB pensions and will now receive slight increases.

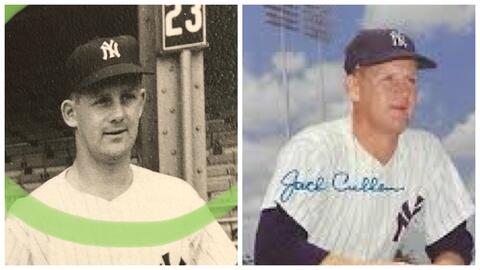

John “Jack” Patrick Cullen, who turns 82 in October, is among the men impacted. A native of Newark, NJ, Mr. Cullen graduated from Belleville High School in 1958.

When reached by phone, Cullen said he moved to Butler when his wife of 57 years fell and broke her hip. It’s a town he describes as “small, like a mining town up on a hill.”

During his career with the New York Yankees, in 1962, 1965 and 1966, Mr. Cullen appeared in 19 games, all but nine of them in relief. He recorded four wins, one shutout, one save and two complete games in 73 and one-third innings of pitching. For his career, he had a sparkling Earned Run Average of 3.07.

Mr. Cullen doesn't receive a traditional pension because the rules for receiving MLB pensions changed in 1980. Cullen and the other men do not get pensions because they didn’t accrue four years of service credit. That was what ballplayers who played between 1947 – 1979 needed to be eligible for the pension plan.

Instead, they all receive nonqualified retirement payments based on a complicated formula that had to have been calculated by an actuary.

In brief, for every 43 game days of service a man had accrued, he gets $718.75 up to the maximum of $11,500. And that payment is before taxes were taken out.

As for not knowing about the 15% increase in the payment, Cullen said the following in a phone response:

“I didn’t know about it, but I figured when they’d get a new (collective bargaining) agreement, I’d eventually get the money.”

Cullen didn't know exactly how many days of service he accrued.

“I never added it up — but I guesstimate it amounted to 120 days over three seasons.”

Based on that, before the new CBA increased the stipend, he would have gotten a gross payment of approximately $1,875. After taxes, his net would probably have been $1,280 per year.

So with the increase, his new net is approximately $1,475.

“Inflation is eating away at everything these days, the price of meat, the cost of gas, the price of steak, it all eats away at your wallet.”

Cullen said he might have accrued more service time, but he served in the military and was stationed at Fort Dix.

While Cullen’s exact salary isn’t known, most players of that generation earned $12,000. Meanwhile, in the recently negotiated CBA, the minimum salary was increased by 23.8 percent, to $700,000.

“Listen, something is better than nothing,” he continues, “but we got squat all those years before 2011. I am thankful for the increase, however nominal it is."

What's more, the payment cannot be passed on to a surviving spouse or designated beneficiary, so neither Cullen's wife, Layne, nor his daughters, Debbie and Maureen, will receive that payment when he dies.

“Where’s the justice in that?” he said. “I mean, she’ll survive without it, because we’ve managed to save a few bucks. We’re not poor, but we’re definitely not rich either,“ Cullen said.

These men are also not eligible to be covered under the league's umbrella health insurance plan.

They are being penalized for playing the game they loved at the wrong time.

Cullen put things in perspective: “I’m not crazy about the situation with me and the 500 other guys, but at least it’s not the situation in the Ukraine. In the big picture, watching women carry their newborn babies out of a hospital that Russia just bombed is a lot tougher.”